Devín Gate to Freedom

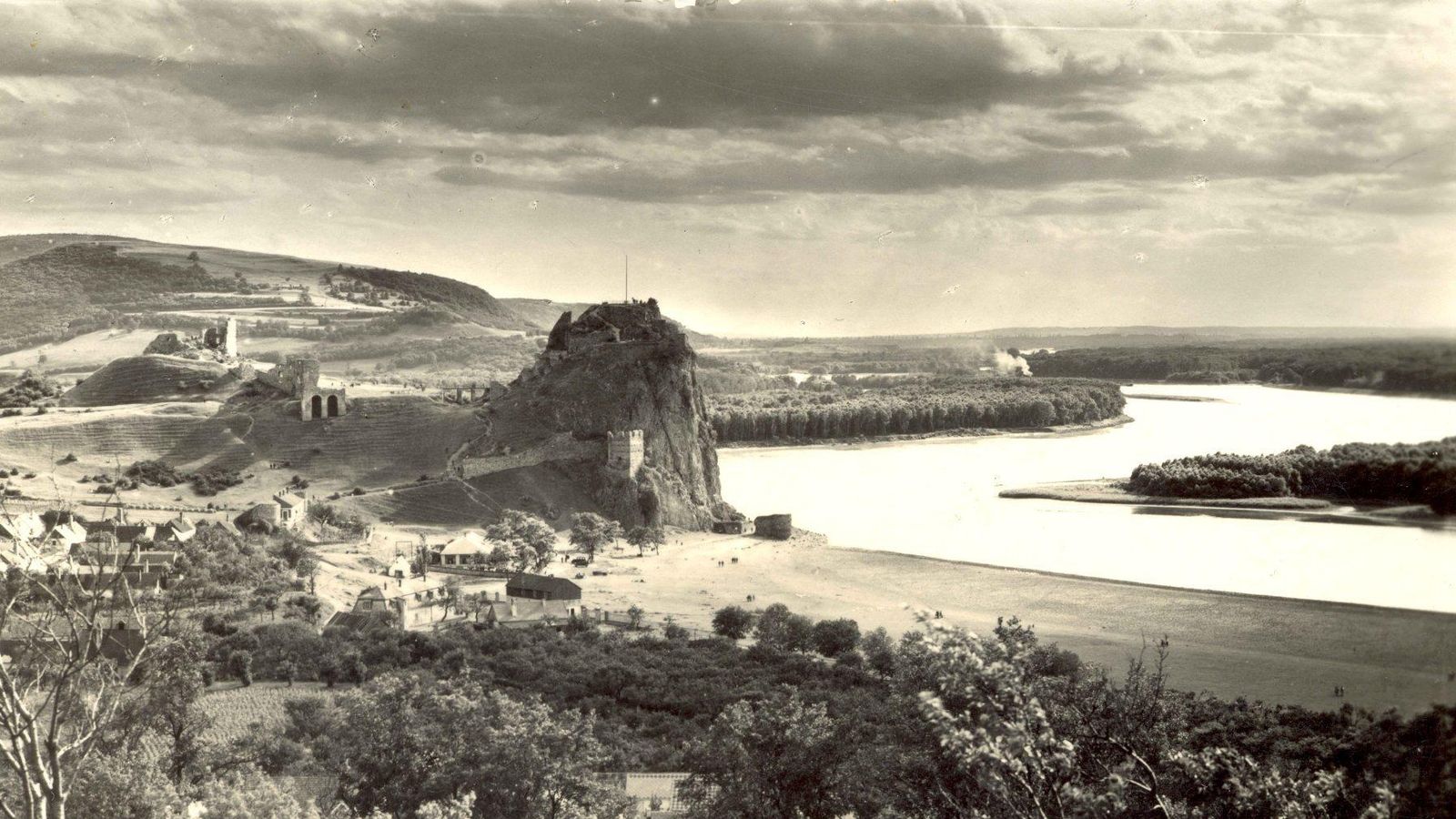

Devín was always a border point and an intersection. It was standing on the borders between kingdoms, then countries, but, during the second half of the 20th century, its place was on the border dividing whole Europe into the so-called Western and Eastern blocs. The Iron Curtain with its name given by Winston Churchill finally did not protect the Czechoslovak Republic from the attacks of the western enemy. In fact, it was closing the door to freedom to its own inhabitants. Many people were looking for a gate to freedom just near Devín, the confluence of the Morava and Danube rivers, for the local terrain and natural conditions.

Since 1938, Devín and Petržalka belonged to the German Empire and the then border between Germany and the Slovak State was running across the south-western slope of Devínska Kobyla – its parts Skala, Pieskovec (Sandberg) – and the northern slope along Karlova Ves down to the Danube River. After the end of the war, both Devín and Petržalka became a part of the renewed Czechoslovak Republic again and the border between Czechoslovakia and Austria became a part of the Iron Curtain no later than in February 1948. In accordance with the communistic ideology, Austria had then represented a member of the capitalistic West and the enemy of socialism.

There were border barriers built in 1950 and the territory between the barriers and the state border was declared a restricted zone. The height of the Iron Curtain was 2.2 metres, at some points even three metres. It was restored every five years since that was the defined lifetime of barbed wire. High voltage, signalling systems, and guard dogs were used there. The system was inspired by the Nazi concentration camps and Soviet gulags.

The Act on Protection of State Border was approved in 1951 which granted border guard units the right to prevent citizens of Czechoslovakia from fleeing across the border even at the expense of their lives.

The zone along the border with Austria with the length of several kilometres was a death zone. Here it was allowed, even ordered to shoot own citizens trying to flee across the border.

The Act on Protection of State Border was approved in 1951 which granted border guard units the right to prevent citizens of Czechoslovakia from fleeing across the border even at the expense of their lives.

The zone along the border with Austria with the length of several kilometres was a death zone. Here it was allowed, even ordered to shoot own citizens trying to flee across the border.

Members of the border guard units were often young men at the age of 18 who were forced to shoot their compatriots. Killing somebody was rewarded by decoration and leave. Failure to kill was punished by a stay in the military prison in Sabinov. In Czechoslovakia, 280 people died when trying to flee and 654 when watching the border. Just a few tens of people succeeded to flee.

Josef Hlavatý with his family was one of them. His story belongs to the stories documented in detail and just his destiny can be used for illustrating the extreme risk to be faced by the individuals, but often the whole families that worked up the courage to flee through the “death zone”.

In 1988, Hlavatý’s wife travelled with one child to Yugoslavia and Josef with his son at the age of three and his parents pretended to spend their holidays camping in Southern Slovakia. Josef was carrying a dismounted hang-glider constructed by himself on the roof of his car.

They hid the tubes in a forest near the state border and camped beside the lake. Josef and his father assembled the hang-glider in total dark and silence in circa 15 minutes. Josef strapped to himself three-year old David; it was the very first flight of the kid.

A short, just seven-kilometre-long distance was waiting for the two-man crew of the hang-glider with the maximum flying speed of 50 km/hour in the maximum height of 2,000 metres. However, Josef lost his course shortly after the start in total darkness without any positioning system. He corrected his course at dawn, and he realized that, for a certain time, they flew not through the border, but along with it.

He headed for the light, but it was a mistake as he soon understood. A watchtower appeared circa twenty metres from him. Armed soldiers aimed spotlights at the hang-glider and started sirens.

Josef intuitively turned his hang-glider to the dark; he lost hist speed and height, but he succeeded in staying just about the trees, circa 50 metres above the ground to avoid radar detection.

After a while, he spotted lights of an Austrian railway station. Immediately after the landing, he took his son and run to hide in bushes since a Czechoslovakian helicopter flew over their heads. If he hesitated whether to land it would have been very probable as he recollected that the helicopter would pull the hang-glider to the ground intentionally by the propeller whirl to pretend it was an accident and propaganda could write that a fleeing man killed both himself and his son.

Meanwhile, the Josef’s wife with the other child jumped out of the window of a hospital in Yugoslavia since a diligent tour delegate was waiting for her at the entrance. The family joined together after two months. Despite the fall of the Iron Curtain in December 1989, Josef and his wife decided to stay in Austria.

Their attempt for escape was successful. However, hundreds of people trying to get free did not succeed and paid for that with their lives. Devín will be a witness of such dramatic stories forever.

Text author: Andrej Barát

More castle history

December 1989 at Devín: The Human Chain and the Fall of the “Iron Curtain”

Devín, once a symbol of a divided world, became in December 1989 a witness to moments that brought hope and freedom. The human chain of students and the fall of the “Iron Curtain” remain reminders of courage and faith in a better future. A Remarkable St. Nicholas Day...

The Iron Curtain Casualties Memorial Was Unveiled by the Queen

On 23 October 2008 during her state call in the Slovak Republic, Elisabeth II, the Queen of the United Kingdom, unveiled the Iron Curtain Casualties Memorial under the Devín Castle at the place where the Iron Curtain used to stand. Construction of the Memorial was...

Changes to the Borders Followed Changes to the States

The state border under Devín was copying dramatic development in the past centuries. The Morava River represented the border between Austria and Hungary in the period of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy until the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic. At those...