Devín Castle 110 Years of Archaeology

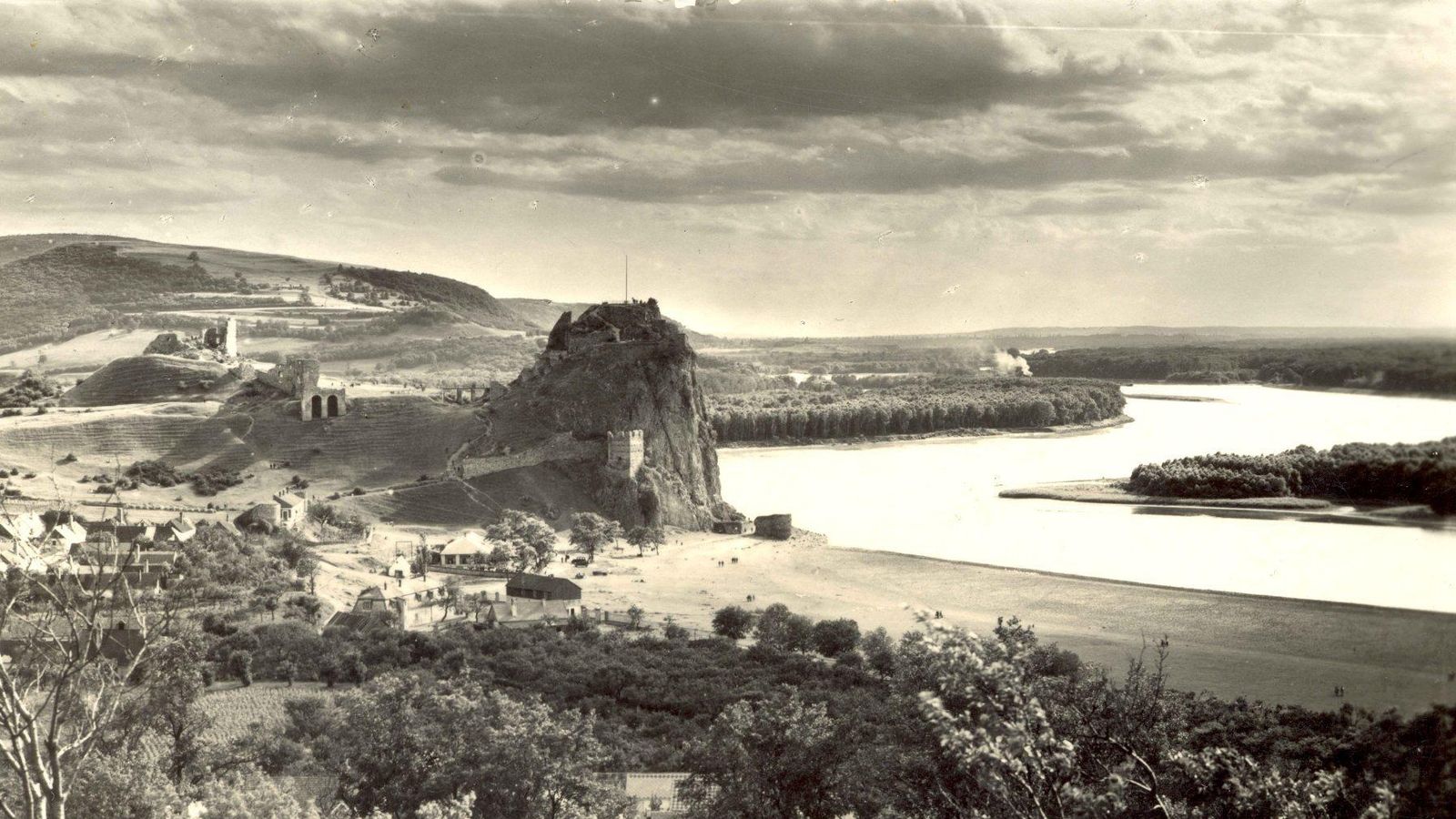

In 2023, there is a symbolic connection of 110 years between the period of the first archaeological activities in the ruins of the castle looming at the strategic point above the confluence of the Morava and Danube rivers. The archaeological journey of the Devín Castle started at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1809, the Napoleon’s troops entered the lives of Devín inhabitants and that was the end of the noble settlement. Ruins of the originally royal castle and remains of palaces and farm buildings owned by the Garay family, counts of Jur and Pezinok, Báthory, Keglevič, and Pálffy families were decaying for several years. In the dynamic 19th century, they became a symbol of the oldest history of our country and Slavonic solidarity with a strong tradition of Great Moravia. This culminated with the well-remembered Štúr movement’s walk on Devín on 24 April 1836. This period was associated with the discussion about localizing Velehrad and Dowina and about the possibility of considering Dowina from the Annals of Fulda and Devín (1) on the Morava River the same.

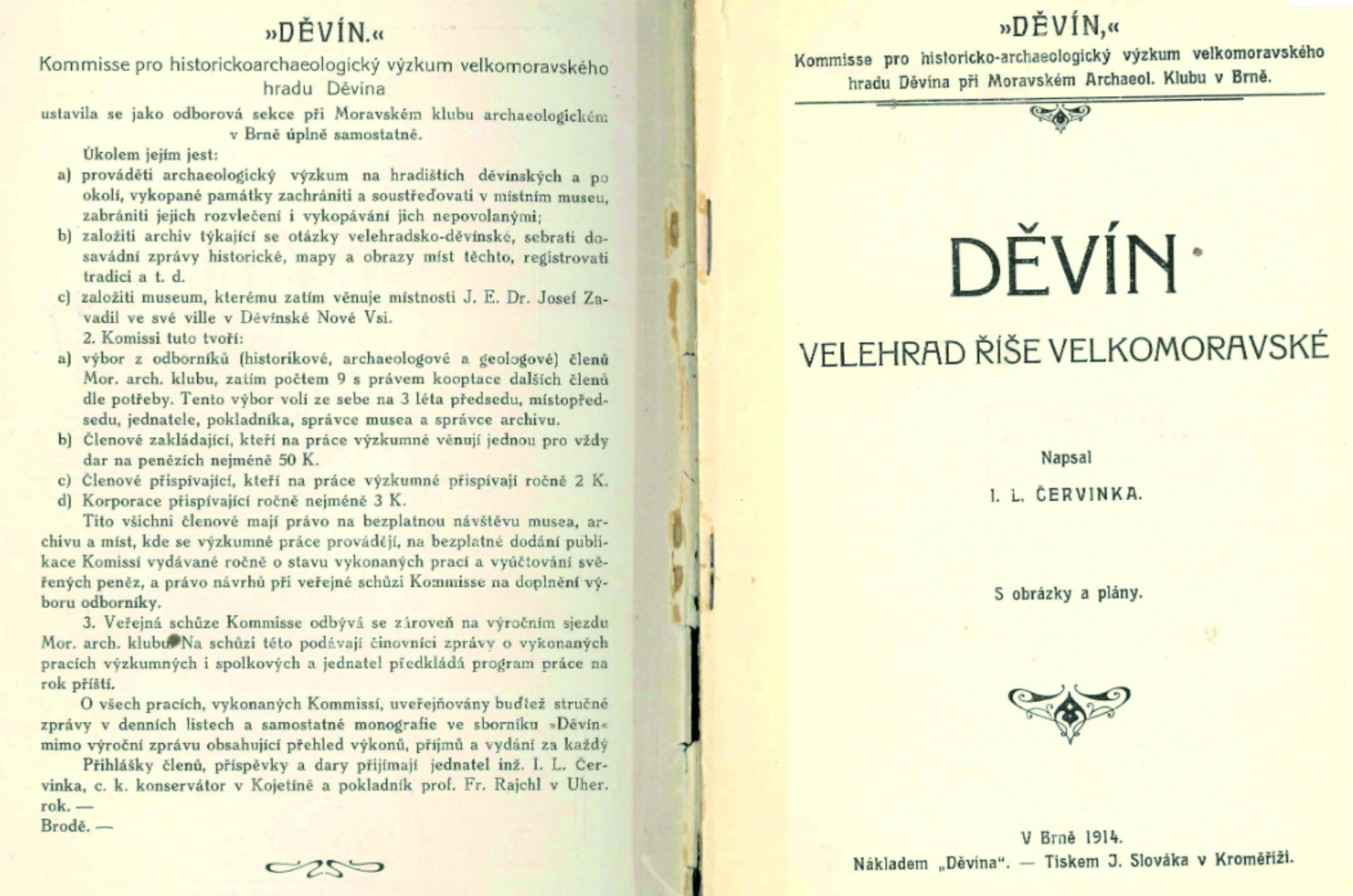

In the 80s of the 19th century, the attention of the polyhistor Josef Zavadil was drawn to the Morava mouth and western slopes of Devínska Kobyla. His interest in Devín was aroused by the study titled Děvín a Velehrad. Dva hrady velkomoravské (1902). In this study, its author I. L. Červinka cast doubt upon considering Velehrad – a seat of the rulers of Great Moravia – and the current Old Town at Uherské Hradiště the same and was the first person who said, “this original town or castle should be looked for beyond the current Moravia border, just like the Devín Castle at the Danube River” (2, 3). J. Zavadil adopted Červinka’s ideas and started to prepare the ground for comprehensive archaeological research. He succeeded in persuading even the members of the Moravian Archaeological Club which resulted in founding the Committee for Historical/Archaeological Research of Děvín, Castle of Great Moravia, in 1913 (4). The Committee was about to found an archive and museum dealing with the so-called Devín issue (5). In the said year, the first excavations supervised by J. Zavadil and I. L. Červinka were made there and the settlement of the La Téne culture, Roman era, and the period of Great Moravia was identified on the Devín hill (6).

The other planned works were interrupted by World War I. Research activities were recovered as late as in 1921, this time already under the baton of the Czechoslovak State Archaeological Institute. I. L. Červinka conducted research on the south-eastern hill and around the eastern gate. A cemetery dated back to the 10th to 11th centuries was discovered there with a stone building interpreted later as the Great Moravian Church situated thereunder. After the end of the research in August 1922, field works were interrupted for ten years.

Between 1933 and 1938, patronage over the next works on the Devín hillfort was taken by the Office for Monuments Conservation in Slovakia and Czechoslovak State Archaeological Institute. Prominent experts of those times – J. Eisner (head of the research), V. Mencl, J. Böhm, A. Loubal, V. Ondrouch, E. Šimek, V. Wagner, and D. Menclová – participated on the research. They were working on several places of the hillfort as well as in the area of the Danube dock under the Nun Tower. As proven by the research, the Devín hill was settled from ancient to modern times. In 1938, Devín was ceded to the German Empire within the Munich Agreement.

1_HARMADYOVÁ, Katarína. Výskum na hrade Devín v medzivojnovom období.

In NEUMANN, Martin – MELLNEROVÁ ŠUTEKOVÁ, Jana (eds.). Dejiny archeológie. Archeológia v Československu v rokoch 1918 – 1948.

Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave, 2020, s. 356-370.

2_ČERVINKA, I. L. Děvín a Velehrad. Dva hrady velkomoravské. Studie topograficko-archaeologická.

Kroměříž : Národní tiskárna Jindřicha Slováka, 1902, s. 63.

3_ZAVADIL, Josef. Velehrady Děvín a Nitra. Příspěvek k určení polohy hlavního města velkomoravského. Kroměříž : Jindřich Slovák, 1912.

4_ČERVINKA, I. L. Děvín. Velehrad říše velkomoravské. Brno: Nákladem „Děvína“, 1914.

Archaeological Dowina in the Second Half of the 20th Century

Signing the purchase contract with the last castle owner Mikuláš Pálffy is the important milestone in Devín’s history of the 20th century. In 1935, the Czechoslovak Republic thus became the owner of the Devín Castle. A few years later, the situation changed dramatically, and, during the war, the castle became a part of the German Empire (1938 – 1945). Besides other things, remains of the amphitheatre on the western slope of the castle hill remind us of World War II. Parts of the standing stone castle walls were also destroyed during its construction. To the contrary, peace celebrations after World War II (first of them in July 1945) restored the Devín’s symbolic meaning of the human and civil freedom. In the post-war period, questions regarding restoration of castles and historic monuments were asked again in Czechoslovakia. The expert committee of the State Archaeological Institute had a meeting in Martin in the spring of 1950 to examine the possibility of opening archaeological research at the Devín Castle. The academic, archaeologist Ján Dekan (together with Ľudmila Kraskovská from BCM in Bratislava) became the head of the research. In February 1961, Presidency of the Slovak National Council designated the Devín Castle as a Slavonic hillfort a national cultural monument.

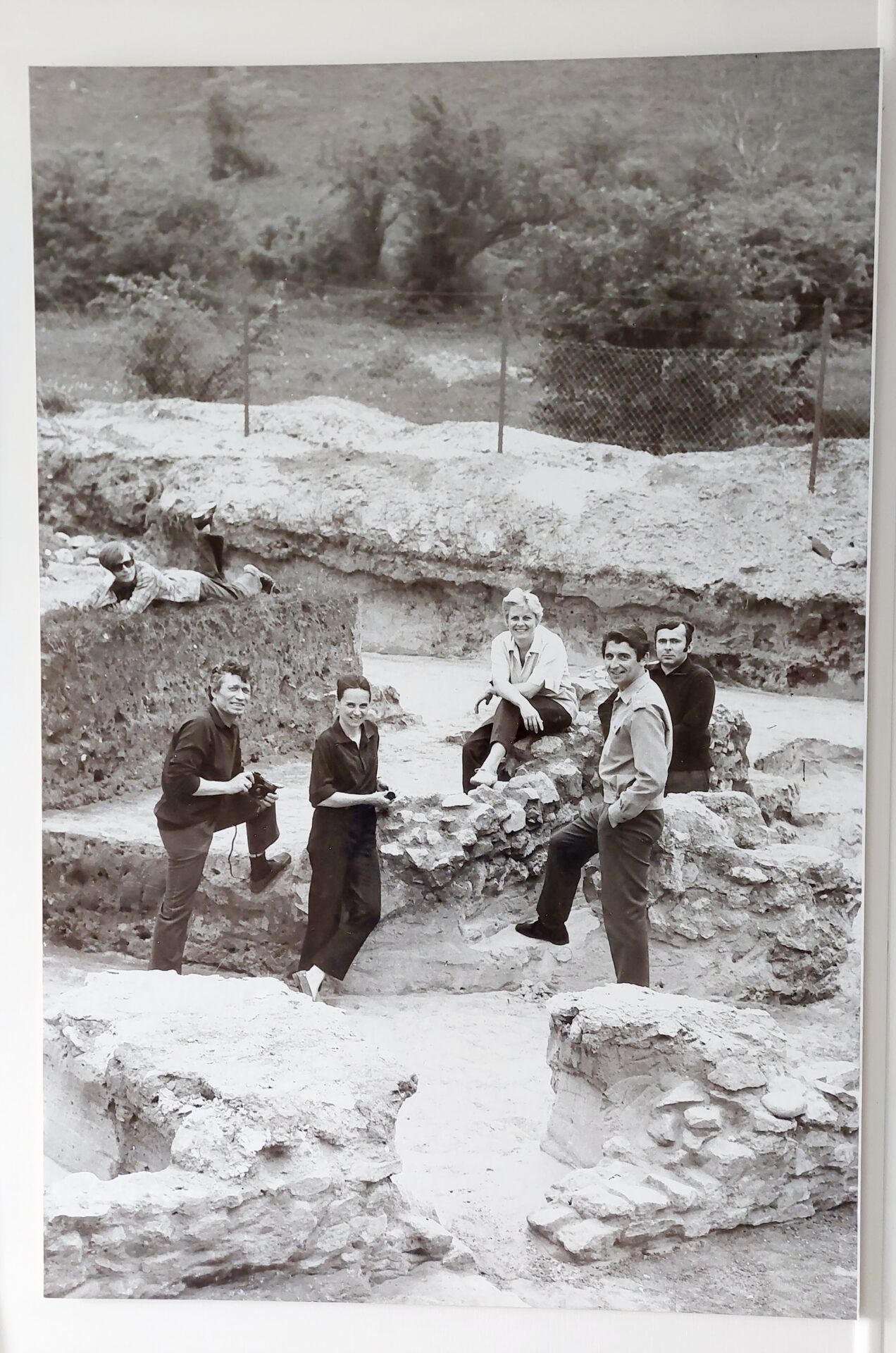

In 1965, patronage over the research at the Devín Castle was taken by the Bratislava City Museum to provide monuments renovation on the castle site. Systematic archaeological research was started in 1965 and it was led by Veronika Plachá for more than four decades (1).Archaeological works were particularly focused on the Middle and Upper castles, and they have, under her supervision, brought many finding situations from various periods from the ancient times to the Roman era to modern times. Along with that, reconstruction works provided by the Slovak Institute of Monuments Care and Nature Protection in Bratislava started in the 70s of the 20th century.

In 1965, patronage over the research at the Devín Castle was taken by the Bratislava City Museum to provide monuments renovation on the castle site. Systematic archaeological research was started in 1965 and it was led by Veronika Plachá for more than four decades.1 Archaeological works were particularly focused on the Middle and Upper castles, and they have, under her supervision, brought many finding situations from various periods from the ancient times to the Roman era to modern times. Along with that, reconstruction works provided by the Slovak Institute of Monuments Care and Nature Protection in Bratislava started in the 70s of the 20th century.

Archaeological research was conducted by other personalities of the Slovak monuments restoration and architecture: Jana Hlavicová (2), Andrej Fiala, Jitka Jezná, and, last but not least, Alfréd Piffl. Archaeological works both in the castle and in the municipality were conducted by the archaeologist Igor Keller as well. The other archaeologists and experts from other disciplines participated on the research and the processing and publishing of the results all of whom significantly contributed to revealing history of the castle site and the Devín Gate.

In 1985, the castle was opened for the public. In these years, some other important findings and information (uncovering the entire ground plan of a building with three apses on the castle hill, carbonated bread, and so on) were discovered thanks both to the review and new research (3). Along with that, some other stages of the monuments restoration, conservation, static security, and presentation of the castle site (the Upper Castle, Renaissance tower – Maiden Tower, Middle Castle, castle well, etc.) took place.

Since 2006, research at the Devín Castle was led by Katarína Harmadyová in cooperation with Denisa Divileková (4). Later archaeological works brought findings of other architectures from the High Middle Ages (e.g., the tower with a knife-edge from the 13th century or first half of the 14th century) and well-preserved situations from the Roman era or Early Middle Ages. The restored upper part of the castle was opened for the public in 2017. The research and long-time persistent work of Veronika Plachá and Katarína Harmadyová have been followed by the ongoing archaeological research in the Lower Castle with another archaeological team.

1_HARMADYOVÁ, Katarína (zost.). Devín Veroniky Plachej. Zborník k životnému jubileu PhDr. V. Plachej. Bratislava: Múzeum mesta Bratislavy, 2017.

2_PLACHÁ, Veronika – HLAVICOVÁ, Jana. Devín. Banská Bystrica: Perfekt, 2003.

3_Mestské múzeum v Bratislave.120 rokov. Jubilejný zväzok. Bratislava, 1988

4_DIVILEKOVÁ, Denisa – HARMADYOVÁ, Katarína. Stredoveké a novoveké hospodárske a obytné objekty z hradu Devín. In Archaeologia historica, 2012, vol. 37, s. 379-390.

Report from Interreg SK — AT Archaeological Research

Archaeological research within the project Culture Across – Cultural Bridges across the Morava Riveris conducted from June 2021 to September 2023. Here is the report thereof in the form of a summary of the most important preliminary results.

What are our research methods?

Archaeological research consists of the non-invasive (georadar) and invasive (excavations) parts in the Lower Castle and post-excavation research of the already excavated findings and identified spatial finding relations. Archaeological findings can be surveyed comprehensively thanks to our extensive multidisciplinary team and various research tools (georadar survey, lidar imaging, archaeological excavations, typology, trace analysis of bone tools, petroarchaeological optical microscopy, osteoanthropological, palaeontological, and biomolecular archaeological methods, archaeobotany, archaeoichthyology, accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating, carbon and nitrogen isotope ratio mass spectrometry, conservation research, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy).

What did we find out?

There are three significant groups of findings among the discovered movable and immovable monuments from the period starting in the 6th millennium BC and ending in the second half of the 2nd millennium AD, which differ from one another from the time point of view. They represent cemetery activities in Eneolith (turn of the 4th millennium BC), settlement activities in the late part of the La Téne culture (second half of the 1st century BC), and cemetery activities in the Early Middle Ages (end of the 8th to 10th centuries).

Almandine

The gemological analysis – refractive index of light, observations in the UV light, research under the gemological microscope, Raman and photoluminescent spectra – has proven that this finding was almandine, probably from Asian deposits. Scratches in its convex part show that it was embedded in a ring. The post-excavation analysis of the place of finding can contribute to dating this semi-precious stone in the cabochon cut.

The size is 8.57 × 7.19 mm, the height is 2.10 mm. Photo: Bratislava City Museum

Golden ring

The X-ray fluorescent spectroscopy of this simple ring showed that the alloy consisted of 91% of gold, almost 8% of silver, and the rest is copper, tin, and iron. Similarly to the almandine finding, dating of this finding is subject to further research.

Outer diameter of the ring is 2.3 cm. Photo: BCM

LiDAR

In the Devín Castle landscape and its nearest vicinity, the airborne laser scanning (LiDAR, eng.) was processed for the first time in the history of this national cultural monument. A specialized visualization with the high resolution (25 cm/px) was used there. These procedures enabled us to identify or point out various, often “invisible” elements of historical landscape structures.

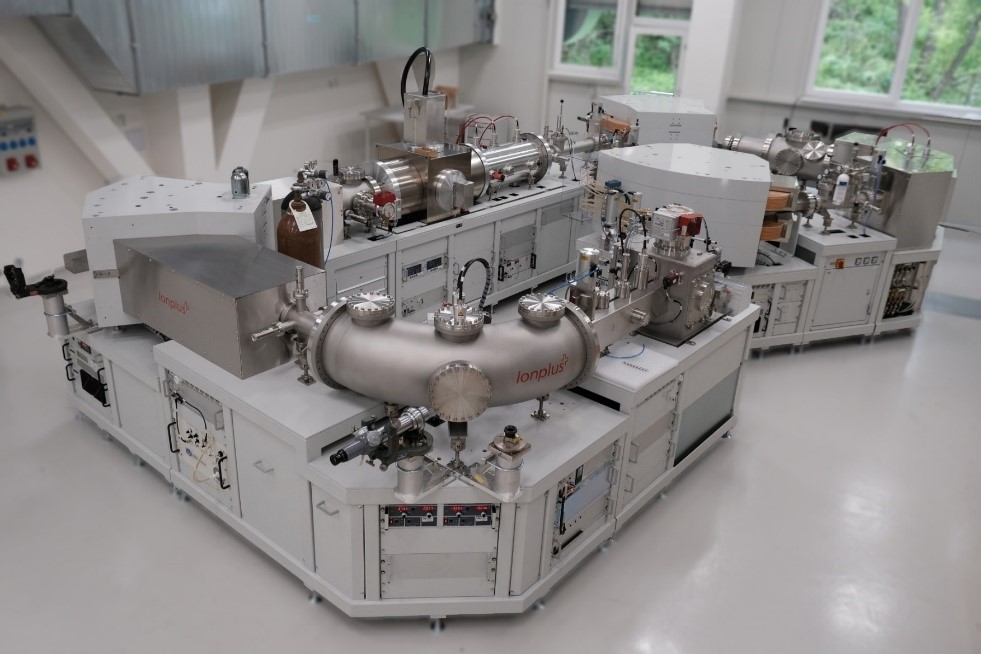

MILEA laboratory

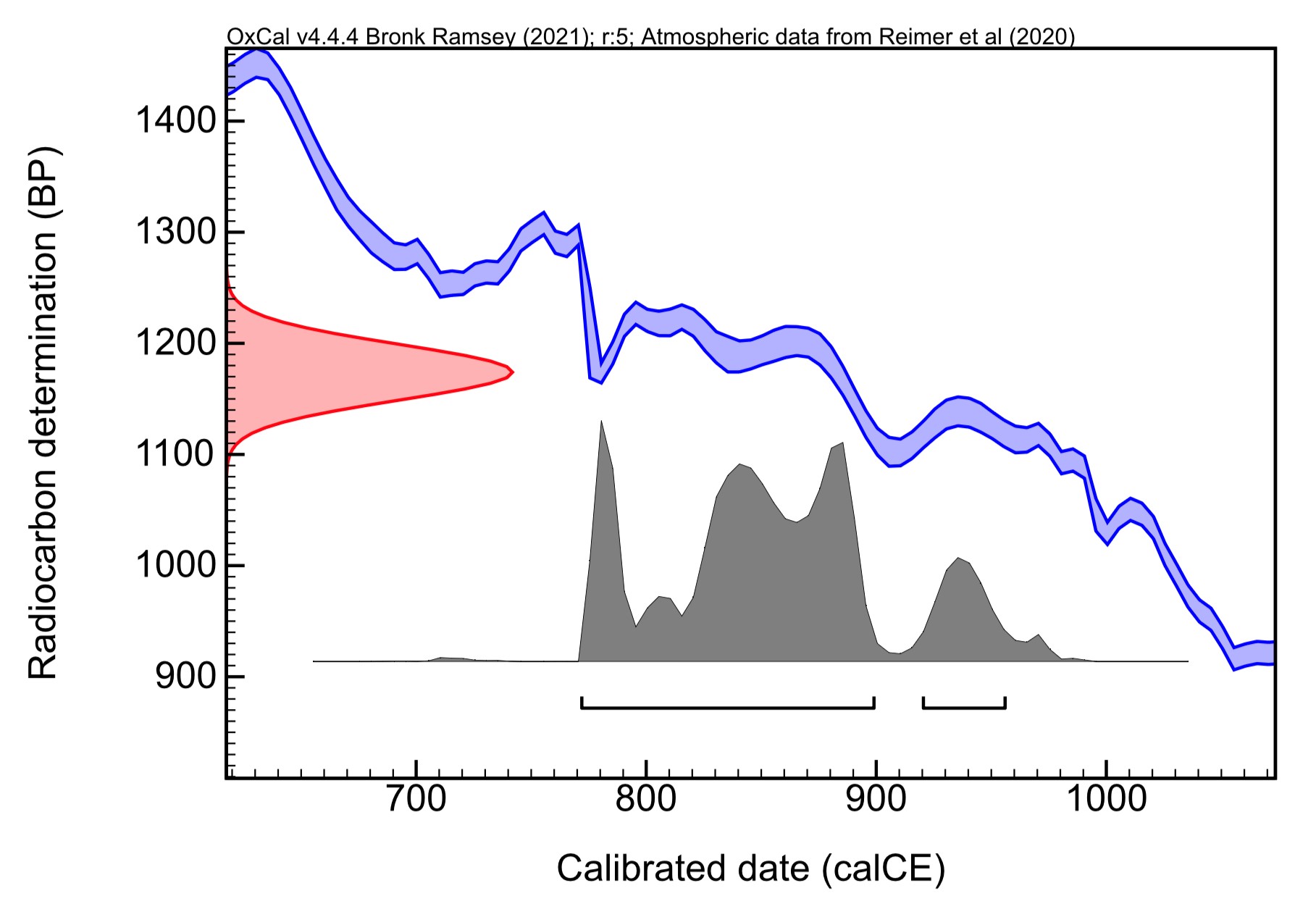

The radiocarbon age of samples from Devín are measured by our colleagues in the MILEA accelerator mass spectrometer in the Nuclear Physics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences. The measured values are converted onto the age in calendar years, and we find out the age of the bones of humans and animals and carbonated remains.

Photo: Kateřina Pachnerová Brabcová (Nuclear Physics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, public research institution)

During the field research, we make cuts through the layers of various sediments. They provide us the information which layers are older, and which are younger. Little pink fragments in the layer above the animal skull are remains after the fire of a burnt clay plaster. After an unspecified wooden building plastered by clay had been destroyed, remains of the plaster deposited above the animal skull. As proven by archaeological research, it was a beef skull. The age of the skull and thus, indirectly, also thin layers of puddle fragments will be examined by radiocarbon dating of the already taken samples of the bones.

During the field research, we make cuts through the layers of various sediments. They provide us the information which layers are older, and which are younger. Little pink fragments in the layer above the animal skull are remains after the fire of a burnt clay plaster. After an unspecified wooden building plastered by clay had been destroyed, remains of the plaster deposited above the animal skull. As proven by archaeological research, it was a beef skull. The age of the skull and thus, indirectly, also thin layers of puddle fragments will be examined by radiocarbon dating of the already taken samples of the bones.

Archaeological probes

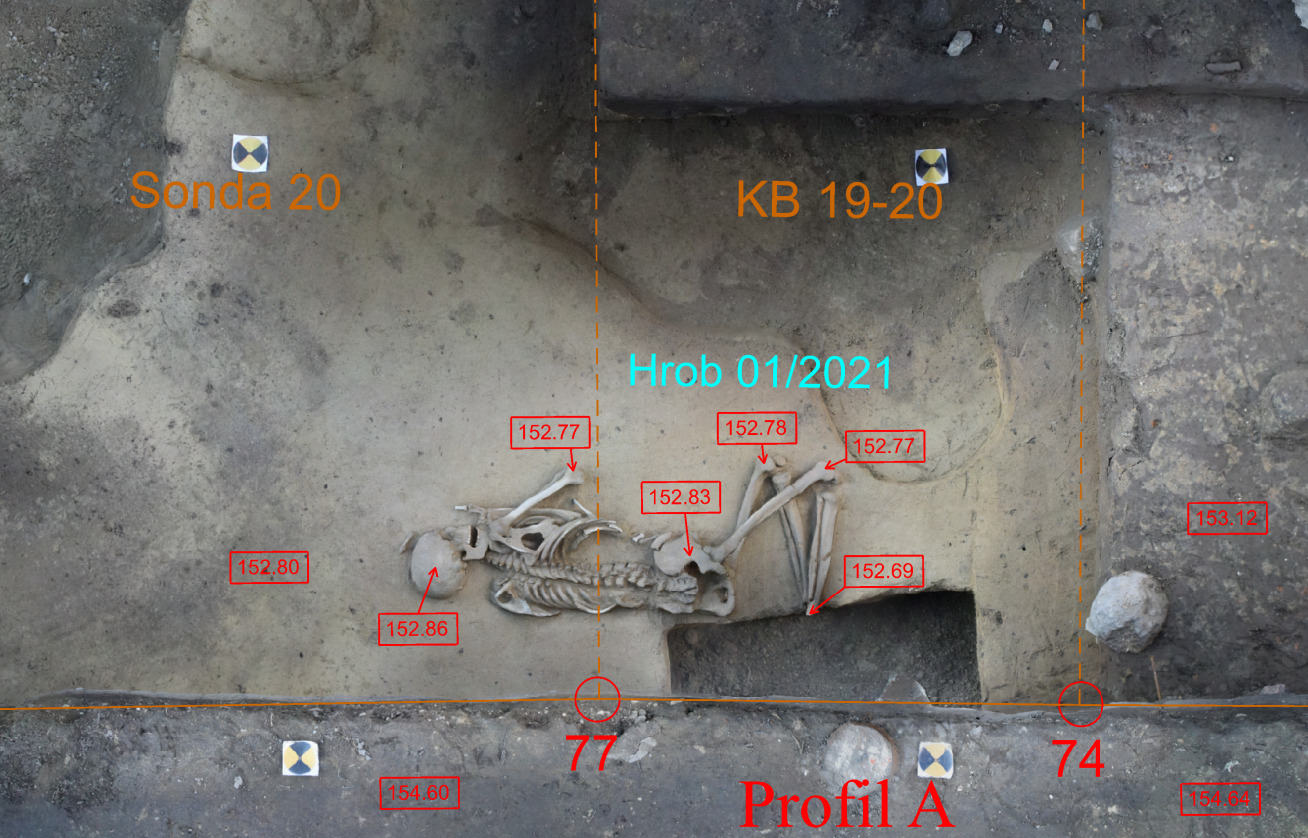

After producing photo and drawing documentation of the ground plan situations on the bottoms of archaeological probes, we are removing sediments (soil) of a different colour. We thus identify shapes of the pits dug by people in the past. As we can see on this photograph made by a drone, there are, for example, two long and narrow foundation trays and various circular pole pits there. Another type are the grave pits. The grave of a mature male on the photograph is dated back to the 8th to 10th centuries AD. It is distorting one of the foundation trays. The building the tray was a part of had ceased to exist long time before the grave was dug.

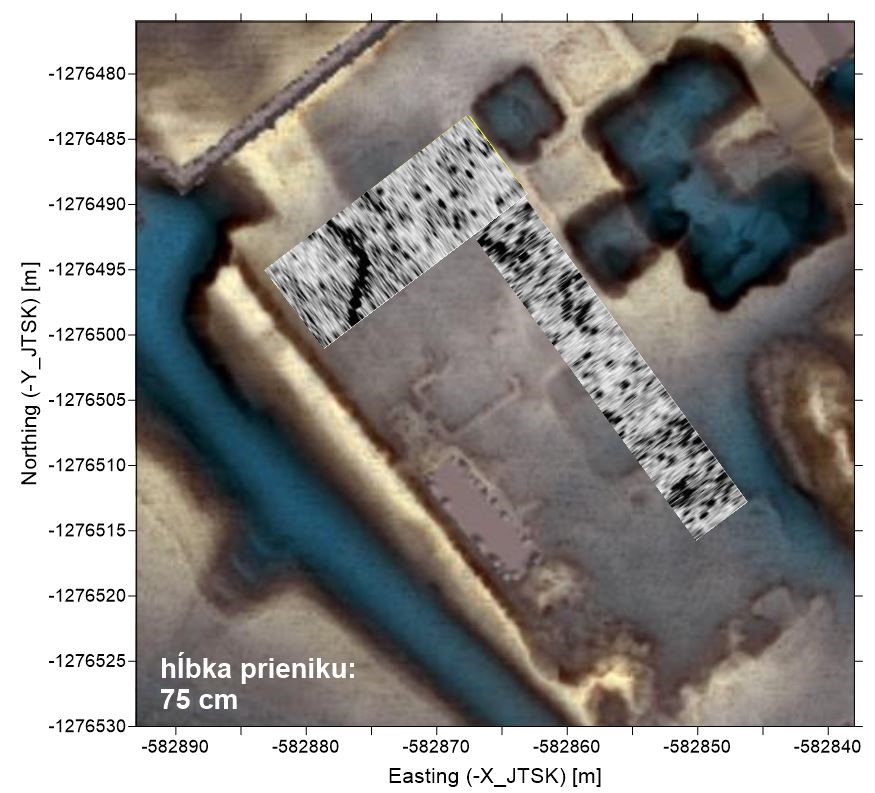

Radargram

Research in the sector 1 also included detailed geophysical (georadar and magnetometric) measurements. They were aimed at researching and detecting subsurface structures that could represent archaeological structures. Two most suitable geophysical methods were chosen for this purpose: measurements using the georadar method (GPR = Ground Penetrating Radar) and measurements using vertical magnetometric gradiometry.

The first Eneolithic grave in the castle site. Will we find more of them?

Graves are the most important monuments dated back to Eneolith (Late Stone Age). They consist of skeleton remains of a male uncovered in November 2021 and another grave finding we started to uncover in August 2023.

Whereas the time connection between the male grave and the human skull having been just uncovered is still subject to considerations upon their mutual spatial relations, our knowledge regarding the male grave is better. No items were found there, indeed, but the skeleton remains as such offer a lot of information. We have found out that it was a healthy adult with no signs of diseases and injuries. Genetically (mtDNA, Y-DNA), he belonged to typical Neolithic and Eneolithic populations as was also proven by radiocarbon (14C) dating. Based on the 14C data, we know that he lived around the period between 3090 and 2900 BC. Upon the measured ratios of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen (C and N), we have found out that his food resources had changed during his life. When he was 11 to 14, his food came mainly from terrestrial sources; however, several years before his death, he had provably also consumed organisms from the water environment and amphibians.

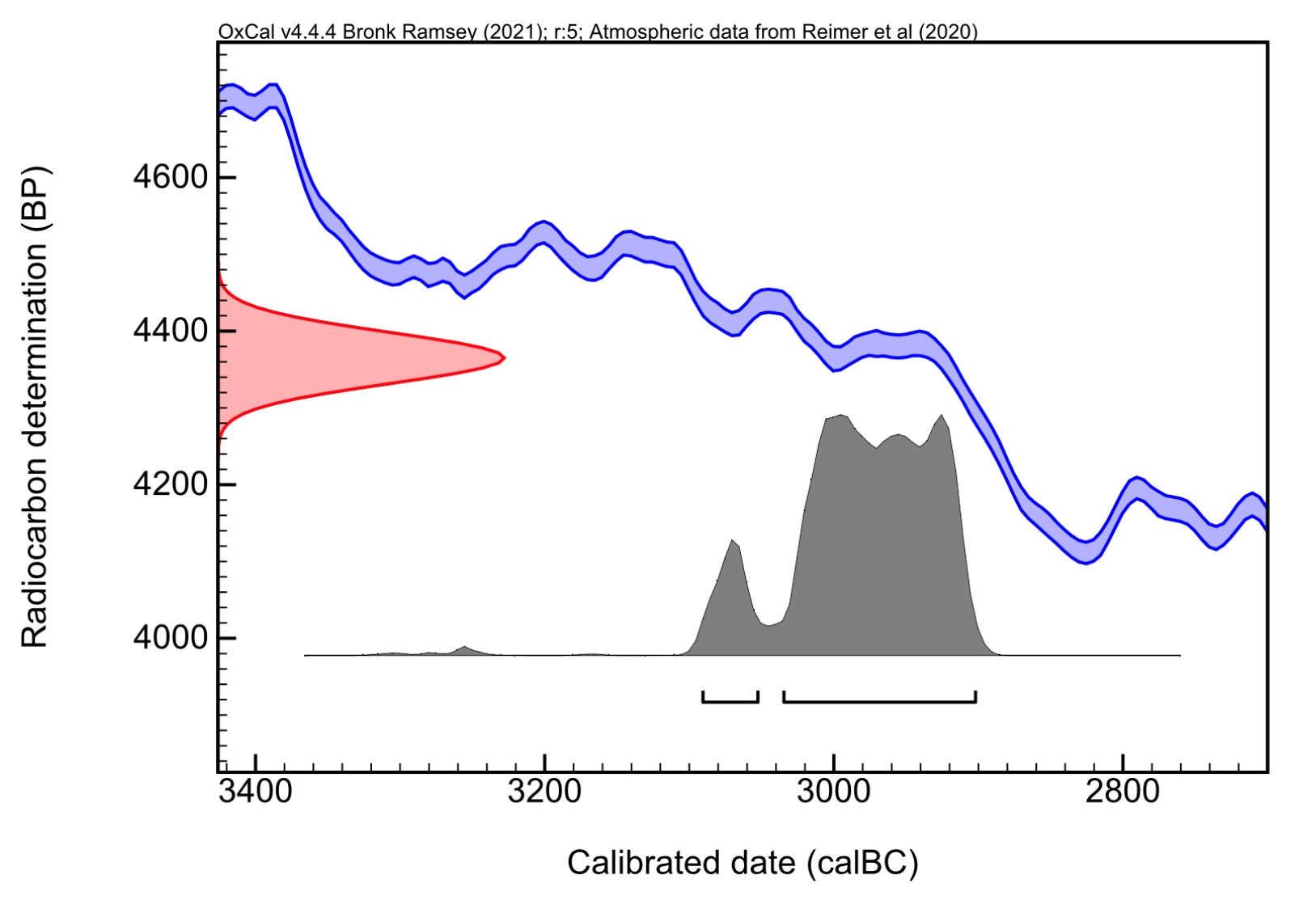

Radiocarbon age measured from a sample taken from a young adult male’s tooth. The vertical axis represents conventional radiocarbon age, the horizontal one represents the calibrated radiocarbon age in calendar years. Based on this analysis, we were able to find out that the male lived around the period between 3090 and 2900 BC.

Graver made of limnosilicite from central Slovakia Neolith/Eneolith. Photo: BCM

Blade made of silicite of glacigene sediments from northern Moravia or southern Poland Neolith/Eneolith. Photo: BCM

Splinter with retouch made of silicite from the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura Upland Neolith/Eneolith. Photo: BCM

Along with the finding of the grave from the Late Stone Age, the castle site settlement in a more extensive time period from the half of the 6th millennium to the 3rd millennium BC is also proven by small stone tools with the size of few centimetres found in 2022, while sieving the excavated sediment. At the same time, they inform us about the long-distance trade with raw materials for tools production.

Scraper made of radiolarith from the Western Carpathians Neolith/Eneolith. Photo: BCM

Contemporaries of the Celtic oppidum in Bratislava

Significant traces of the Celtic settlement which is well know from the other parts of the castle site can be found in the entire researched area between the north-western wall and barrier. Our findings are dated back to the late La Téne culture, from the second half of the 1st century BC. The most significant ones are two clasps with folded little bows, fragment of a large glass bead, a bone semi-product for manufacture of dice, and fragments of painted pottery found in 2022 and 2023. Remains of the buildings from this period are represented by some of the discovered pole pits the vertical wooden framework elements of the above-ground structures were originally situated in. The buildings could have residential or farm function (workshops, storerooms).

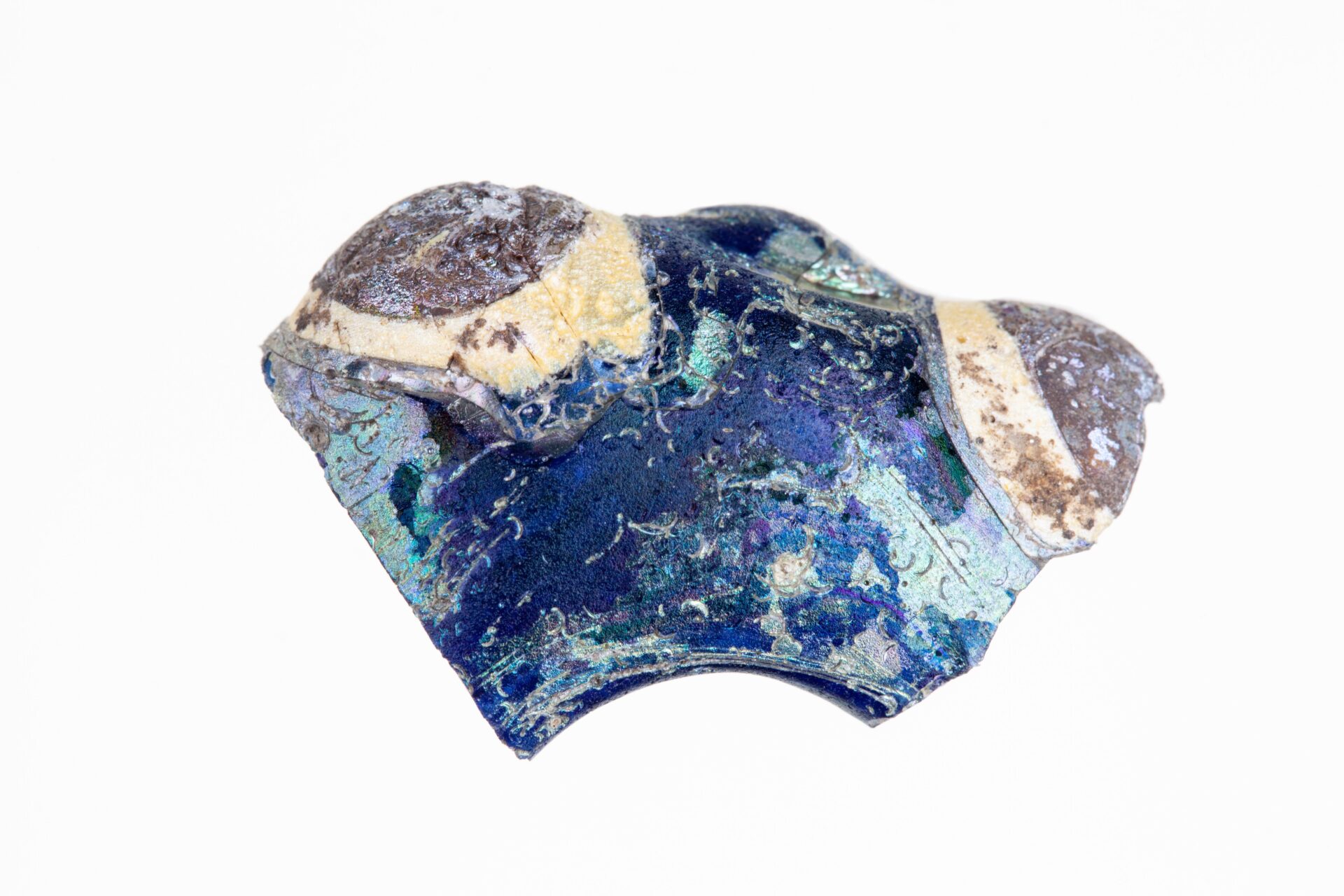

Glass bead

La Téne culture. Photo: BCM

Fragment of a large circular glass bead with the eyes. Circa one fifth of the entire circumference was preserved. The length of the displayed fragment is 2.3 cm.

Clasp

La Téne culture. Photo: BCM

Bronze clasp with a folded little bow (type Almgren 18). The little bow and a part of the clasp winding (left side) were preserved; a needle which did not survive was directed out of the clasp winding. The clasp fitted into the retainer which was partially preserved (right side). Such clasps are also known from other locations of the Devín Castle site from the layers of the late La Téne culture. The length of the clasp is 9.2 cm.

Graves from the Early Middle Ages

In the summer of 2022, we discovered the graves of a male and a child; their mutual distance was circa ten metres. The adult male laid on his back in a wooden coffin without any iron parts. Traces of the coffin were preserved in the form of darker soil. Changes to the bones proved manual work (worn elbow) and health issues (tooth decay, degenerative changes to the vertebrae, ossification of thyroid and costal cartilages).

The male was wearing a simple, corroded iron knife only upon which we were not able to assign the grave a respective time. We did this upon the 14C data, pursuant to which he lived circa from the end of the 8th to the 10th centuries AD. No changes to the food resources during his life were proven by the analysis of ratios of stable C and N isotopes. The measured values can indicate that his food included millet.

A partially preserved skull was found in the grave of a three-year-old child from the end of the 9th to the 10th centuries. Two vessels were found by the child’s feet. The analysis of the soil contained in the vessels could answer the question what was originally therein. Based on the analysis of stable C and N isotopes, the child was breast-fed.

Male’s grave

Early Middle Ages. Photo: BCM

Continuous uncovering of the adult male’s grave form the end of the 8th to the 10th centuries. The dark soil is a remain of organic materials (wood of the coffin, clothes of the buried person).

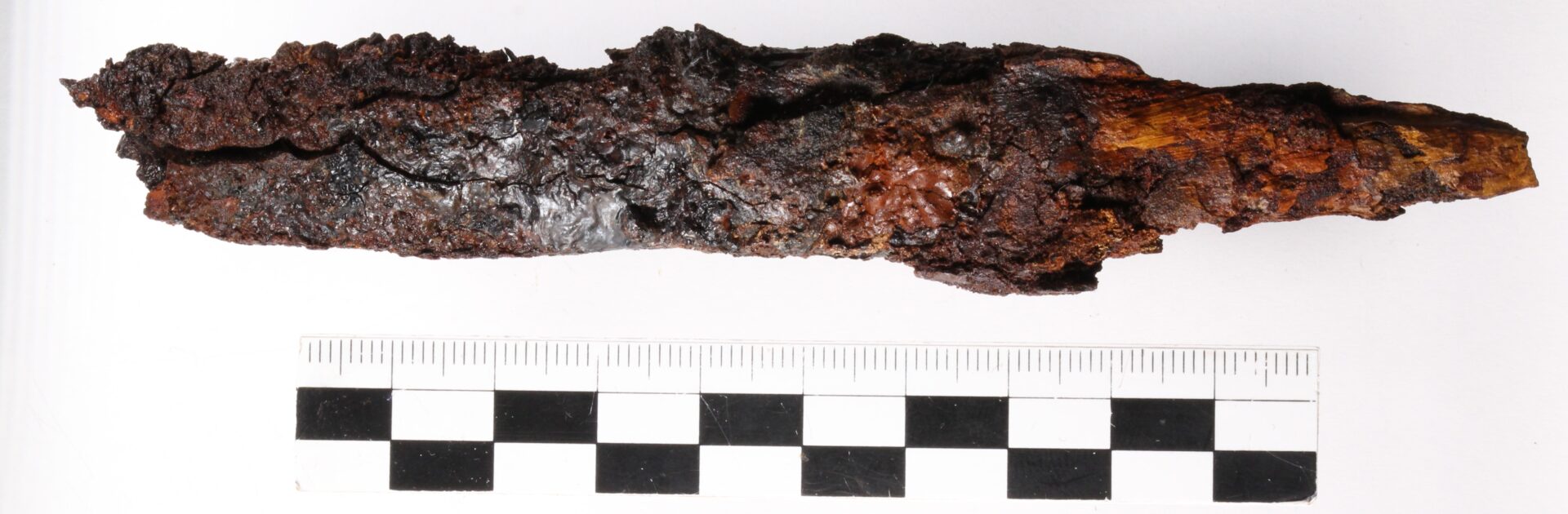

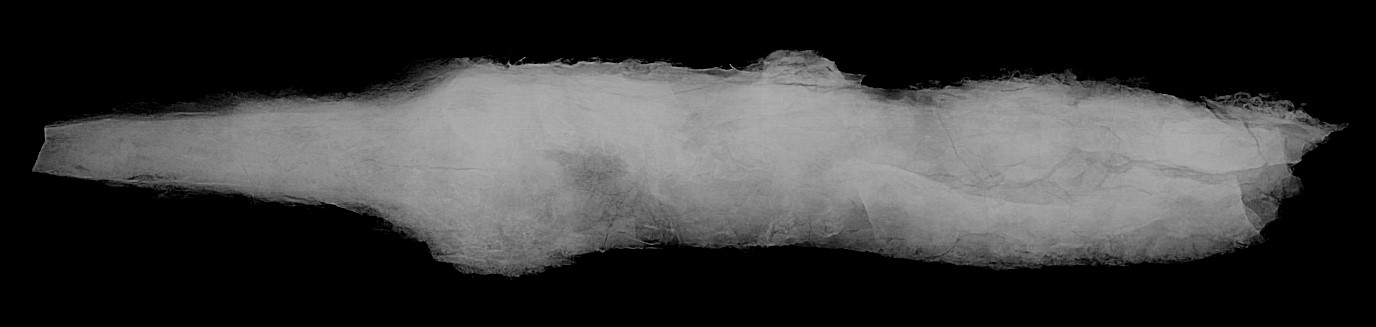

Iron knife

Early Middle Ages. Photo: BCM

The iron knife before the conservation action (upper side), after the conservation action (middle), and its X-ray image (bottom side) documenting extensive corrosion of the item (grey shades). The length of the knife is 14.3 cm.

Ceramic vessels

Child’s grave from the Early Middle Ages Photo: BCM

Ceramic vessels from the grave of the three-year-old child whose bone collagen was dated back to the interval from 880 to 1000 AD using the radiocarbon dating. The height of the vessels is 7.8 and 17.1 cm.

14C dating

Male’s grave from the Early Middle Ages

Radiocarbon dating of bone collagen of the adult male. The horizontal axis represents intervals in calendar years. In accordance with this analysis, the male died somewhere within the interval from 770 to 900 or from 920 to 960 AD.